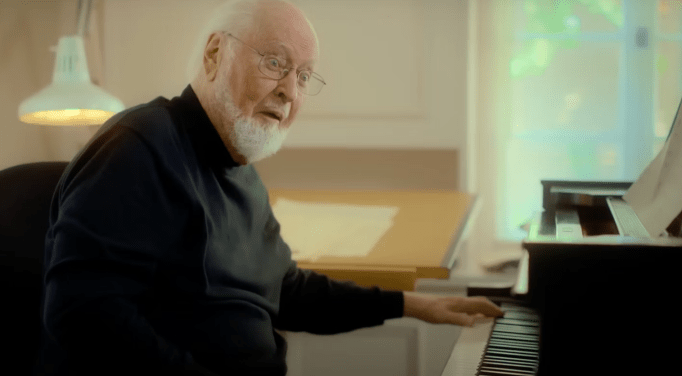

Documentary film “Music by John Williams”, which is currently available on Disney+, looks over the long, illustrated career of one of the best film composers of our time. Since he rose to prominence around the late 1960s, John Williams has steadily advanced as constantly impressing us with many different great film scores, and he is still working even though he is about to have his 93rd birthday early in the next year. Although it simply lets Williams and many other distinguished figures explain and talk about some of his famous works, the documentary is still quite entertaining as effectively presenting one stellar achievement of his after another, and that is more than enough for anyone interested in film music.

During its early part, the documentary gives us the brief summary on William’s early years. Thanks to the encouragement from his musician father and dancer mother, young Williams frequently practiced a lot on piano, and he soon came to show more talent and potential while becoming more passionate about music. Around the time when he joined the US Air Force in the early 1950s, he was already a skilled pianist/composer/arranger, and that was how he came to compose the music for a little military documentary. After leaving the US Air Force, he began to work here and there in Hollywood as a recording session pianist, and you will be surprised to see that he is the one who played the piano in Elmer Bernstein’s Oscar-nominated score for Robert Mulligan’s classic film “To Kill a Mockingbird” (1962) and Henry Mancini’s iconic theme for TV drama series “Peter Gunn”.

As he got hired more and more an arranger/composer in Hollywood, Williams, who was now listed as “John Williams” instead of “Johnny Williams”, eventually went all the way for composing film music around the late 1960s, and the rest was the history. He soon received his first several Oscar nominations within a few years, and one of them was for his score for Mark Rydell’s “The Reivers” (1969), which incidentally drew the attention of a very young filmmaker named Steven Spielberg. When he later made a feature film debut with “The Sugarland Express” (1974), Spielberg eagerly approached to Williams, and that was the beginning of their legendary collaboration which recently impressed us a lot again in “The Fabelmans” (2022).

When Spielberg showed the rough cut of his very next film “Jaws” (1975), Williams was rather horrified by how his Oscar-nominated score for Robert Altman’s “Images” (1972) were utilized in the temp track of the soundtrack, but he created one of the most recognizable movie themes of all time nonetheless. When he played that a bit for Spielberg, Spielberg thought Williams was just kidding, but, what do you know, that simple idea of Williams worked splendidly when it was played by the orchestra during the following recording session, and Spielberg saw how much Williams’ music, which deservedly garnered Williams’ second Oscar (He previously won an Oscar as an arranger for Norman Jewison’s “A Fiddler on the Roof” (1971), by the way), enhanced his film.

After the enormous success of “Jaws”, Williams’s career got boosted much further thanks to another two ground-breaking scores to remember. When he was recommended to a certain close friend of Spielberg, Williams was initially not so sure about whether the movie directed by that friend in question, but then he became quite enthusiastic about that film. Yes, that friend in question was none other than George Lucas, and that movie, “Star Wars” (1977), inspired Williams to create one of the most recognizable works in his whole career which won him the third Oscar.

Meanwhile, Spielberg also worked on something equally special, and Williams quickly came onto the project right after having an amazing time with “Star Wars”. In “Close Encounters of the Third Kind” (1977), Williams was instructed to create an effective five-note motif as a crucial part of not only the whole score for the story itself, and, again, he did not disappoint Spielberg at all with his fabulous result, even though it took some time for him to find the right five-note motif for the movie.

With more big successes thanks to a number of notable films including “Superman: The Movie” (1978), “Raiders of the Lost Ark” (1981), and “E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial” (1982), which won him the fourth Oscar, Williams became all the more popular than before, and then he was selected as the principal conductor of the Boston Pops Orchestra in 1980. His first several years with this orchestra were rather rough because many of the snobbish orchestra members did not regard him that highly, so he eventually quit four years later, but then, what do you know, he returned and then worked with the orchestra till 1993.

And he kept working in Hollywood as usual. After delivering two equally stunning score for Spielberg’s “Jurassic Park” (1993) and “Schindler’s List” (1993), William showed more of the other sides of the immense talent, and it is a bit shame that the documentary does not delve that much into the period after he won his fifth Oscar for “Schindler’s List”. Sure, it is nice to see Chris Columbus’ “Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone” (2001) getting mentioned as expected, but I wish the documentary focused on his rather overlooked gems including the one for Alan Parker’s “Angela’s Ashes” (1999), which was incidentally Oscar-nominated instead of Lucas’ “Star Wars: Episode I – The Phantom Menace” (1999) in that year.

On the whole, “Music by Williams” could show and tell more about its human subject, but the result is quite compelling enough for us thanks to the competent direction of director/co-producer Laurent Bouzereau, who recently gave us HBO documentary “Faye” (2024). After James Mangold’s “Indiana Jones and the Dial of Destiny” (2023), which brought him the latest Oscar nomination (He was nominated no less than 54 times, by the way), Williams suggested that he would soon retire, but then, to our relief, he later said that he will go on as long as possible. Considering his age, he may not live that long, but he is ready to sit and write his music on paper as before (He still does not use computer at all for his work, you know), and we will cherish whatever will come next from him.