On the surface, Akira Kurosawa’s 1963 film “High and Low” simply follows one kidnapping case from the beginning to the end. While the overall result works as a dry but undeniably compelling police procedural, the movie also gives us some revealing glimpses into the social class issues in the Japanese society during the 1960s, and it is certainly one of many high points in Kurosawa’s legendary filmmaking career.

The movie opens with a little private business meeting between a wealthy businessman named Kingo Gondo (Toshiro Mifune) and his several business associates. They want to persuade Gondo to help them taking over their big shoe company, but it later turns out that Gondo has the other idea behind his back. As a matter of fact, he virtually bets all of his assets on this for not only getting richer but also taking over the company for himself.

However, there soon comes an unexpected emergency. Gondo receives a call from someone saying that he has just kidnapped Gondo’s only son. Fortunately, Gondo’s son is actually all right, but it turns out that the only son of Gondo’s chauffeur was kidnapped instead. Gondo immediately calls the police, and several detectives quickly come to his residence, but things become more difficult for Gondo. The kidnapper still demands a big amount of ransom as before, and Gondo naturally becomes quite morally conflicted: Can he really sacrifice all of his wealth for saving his employee’s son?

The first act of the movie is mostly unfolded inside the big living room of Gondo’s posh and expensive residence, but this never feels stuffy at all as Kurosawa and his cinematographers Asakazu Nakai and Takao Saitō effectively use the widescreen ratio of 2.35:1 for generating more drama and suspense across the screen. While the camera usually observes Gondo and the main characters from the distance, the movie subtly conveys to us Gondo’s increasingly impossible circumstance via some effective blocking strategies, and you may be amused a bit by how the movie often shows Gondo on the one or the other side of the widescreen – for accentuating how he feels more cornered as the clock is ticking for him and several others around him.

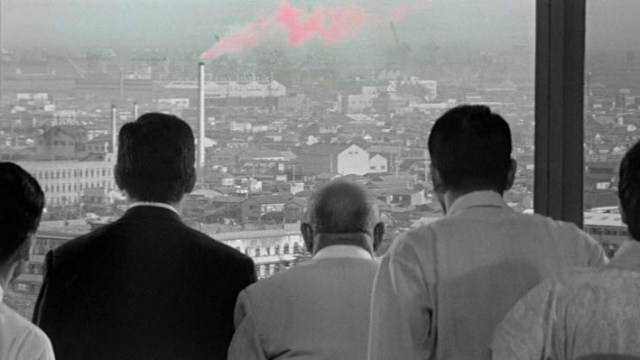

Around its middle act, the screenplay by Kurosawa and his co-writers Hideo Oguni, Ryūzō Kikushima, and Eijirō Hisaita, which is based on Evan Hunters’ 1958 novel “King’s Ransom” (It is one of those 87th Precinct novels written under his pen name Ed McBain, by the way), begins to shift its focus more on a bunch of plain cops working on the investigation of the kindnapping case. Although there are not many clues which may eventually lead them to the kidnapper, they become more determined to do their job as feeling a bit more sympathetic to Gondo’s ongoing plight, and the movie closely follows their steady and diligent joint efforts step by step. Trying to get additional clues as much as possible, they systemically search for any breakthrough, and we become more engaged as they begin to get closer to their target along the story. I especially like the sequence where the two cops and Gondo’s chauffeur respectively try to locate a certain spot associated with the kidnapper, and there is also a particularly wonderful moment when the movie adds a bit of color for an impactful dramatic effect.

In the meantime, the movie reveals a bit on the identity of the kidnapper, and we become more aware of the class gap between Gondo and many others living around his residence. Placed on a high hill, his house looks like a castle flaunting its power and wealth, and this certainly makes a big contrast with the relatively poor neighborhood around the bottom of the hill, where Gondo’s residence is quite visible from here and there. In fact, you will not be surprised much to learn that this striking class gap shown in the film influenced Bong Joon-ho’s Oscar-winning film “Parasite” (2019) a bit, which also makes a big point on the similar class gap throughout its story.

The final act expectedly culminates to the eventual finale of the cops’ investigation, but the film does not lose its coolly detached attitude at all as patiently following the cops’ pursuit of their target in one particular area of the city filled with drug addicts and homeless people. Around this narrative point, the movie becomes a bit noirish with some disturbing sights shrouded in light and shadow, and this resonates more with the original Japanese title: “Heaven and Hell” (天国と地獄).

While Toshiro Mifune is surely the most prominent figure in the cast, he often steps aside for the well-rounded ensemble performance from the various cast members including Tatsuya Nakadai and Takashi Shimura, who are also Kurosawa’s regular collaborators like Mifune. While Kenjiro Ishiyama often steals the show the colorful partner of the detective assigned to the case, Tsutomu Yamazaki is suitably unpleasant as required by his crucial supporting role, and he and Mifune deftly handle the starkly powerful closing scene of the film.

Overall, “High and Low” may not be on par with Kurosawa’s several great films such as “Ikiru” (1952), “Seven Samurai” (1954), “Red Beard” (1965), and “Ran” (1985), but it is still a superlative genre piece to be appreciated and admired for its dexterous handling of story and character coupled of a lot of realism and verisimilitude. From the beginning, I surely knew what it is about, but I got soon engaged and then enthralled by how it is about, and that is what a good film can do in my trivial opinion.