German film “The Lives of Others”, which was re-released in South Korean theaters in this week, takes us into a certain historical period which deserves to be described as “Orwellian”. For more than 40 years, the communist government of East Germany oppressed and monitored most of its citizens as thoroughly and ruthlessly as possible before it was collapsed along with the Berlin Wall in 1989, and the movie chillingly takes us into that grim period via its somber but undeniably powerful fictional story.

The center of the story, which is set in East Germany in the middle of the 1980s, is Gerd Wiesler (Ulrich Mühe), an officer of the East German national security agency. During the opening scene, he interrogates some recently arrested dude, and we observe how he systemically does his job without any hesitation. As a well-experienced interrogator, he surely knows how to break his target step and step, and he does extract a valuable confession from his target in the end.

Not long after he finishes a lecture for a bunch of young officers, Wiesler is approached by Anto Grubitz (Ulrich Tukur), an old friend/colleague of his who is incidentally one of the high-ranking officers in the agency. Grubitz simply wants Wiesler to check on a prominent playwright named Georg Dreyman (Sebastian Koch), and, as observing Dreyman and his actress girlfriend Christa-Maria Sieland (Martina Gedeck) at a local theater where their latest play is performed, Wiesler gets intrigued for sensing something about Dreyman. Although he has not had done anything illegal or subversive unlike some of his colleagues, Dreyman also looks too good to be true, and that is why Wiesler is determined to get to the bottom of his latest target.

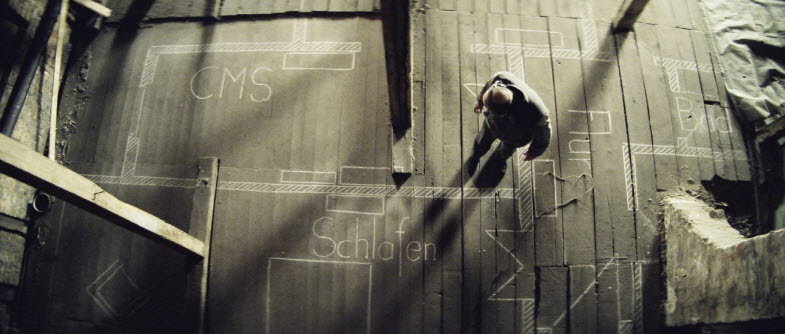

What follows next is a frightening sequence how Wiesler and his men swiftly and meticulously work on Dreyman’s apartment while Dreyman and his girlfriend are absent. Within less than half an hour, a number of small microphones are installed here and there in the apartment, and we get more chilled when Wiesler sternly and effectively warns a close neighbor of Dreyman who happens to witness too much.

Once everything is set and ready, Wiesler patiently monitors Dreyman during next several days, and, to his little surprise, Dreyman turns out to be not so different from him in many aspects. While he does not like much of how the East German government has oppressed some of his colleagues, Dreyman is also a believer who has lots of faith in his government and its ideology just like Wiesler. As a matter of fact, the main purpose of Wiesler’s secret mission is finding anything to ruin Dreyman’s life and career for an influential government minister, who wants more than sexually exploiting Dreyman’s girlfriend behind his back.

In the meantime, we gradually sense that something is changing behind Wiesler’s seemingly unflappable appearance. As he listens upon Dreyman and his girlfriend much closer than before, he somehow becomes a lot more curious about their life, and, what do you know, he even finds himself reading a little poetry book he stole from Dreyman’s apartment.

The beauty of the screenplay by director/writer Florian Henckel von Donnersmarck is that it never spells out whatever is going on inside its dry and taciturn hero while clearly conveying to us his gradual inner transformation along the story. Regardless of whether Wisler has actually yearned for any kind of human connection for years (That seems evident when we look at a small, barren apartment where he lives alone), Dreyman’s human decency and rather innocent idealism clearly affects Wiesler’s heart, and he eventually becomes a hidden guardian angel for Dreyman and his girlfriend – especially after he comes to learn about the main reason of his secret mission.

Of course, the situation soon becomes trickier when Dreyman decided to do something quite courageous against the East Germany government. Having already made us immersed deep into the vivid and realistic presentation of the East German society during the 1980s, the movie adds more tension to the story from that narrative point, and we get all the more engaged as observing how its main characters are pushed to make a choice by their increasingly dangerous circumstance.

Everything eventually culminates to the melodramatic finale followed by no less than three epilogue scenes, but the movie firmly sticks to its calm, restrained attitude as before, and so does Ulrich Mühe, whose subtly masterful acting feels all the more poignant considering that he died not long after the movie came out then won a Best Foreign Language Film Oscar. While never signifying anything on the surface, Mühe gradually reveals a deeply lonely professional who comes to care about his target much more than he ever imagined, and he is also supported well by several good performers including Sebastian Koch, Martina Gedeck, and Ulrich Tukur, who provides some humor and sleaziness to the story as required by his despicably opportunistic character (He is particularly good when his character jokingly scares a certain junior officer for telling a rather irreverent joke about their leader).

On the whole, “The Lives of Others” still moves me a lot although it has been more than 15 years since I watched it early in 2007 and later chose it as one of the best films of that year. Yes, as some critics pointed out at that time, its epilogue part is a bit too long as neatly wrapping up everything in the story, but, boy, it still works enough to touch me as much as before, and I will just let you see it for yourself if you have not watched this wonderful movie yet.