Documentary film “The Space Race” looks into a hidden part of the NASA history which deserves more attention in my humble opinion. Although it could delve more into its interesting historical subject, the documentary did a good job of presenting several relatively unknown figures who were surely trailblazers in one way or another, and it is always interesting whenever these admirable figures gladly tell us about their respective NASA experiences.

The documentary focuses on a number of notable African American astronauts working in NASA, and it can be said that everything was started with a black test pilot named Ed Dwight Jr. Around the time John F. Kennedy was elected as the new president of the United States in 1960, he promised to a bunch of black politicians and activists that his government would include black astronauts in the ongoing NASA space programs, and Dwight happened to be an ideal one for that. Although those white top-ranking military and NASA officials deliberately put some hard limits on their selection process, Dwight was actually able to meet their high standards thanks to his considerable military background, so he eventually got chosen for a bit of racial inclusion in NASA, which, as shown from Oscar-nominated feature film “Hidden Figures” (2016), was usually full of white guys during that period.

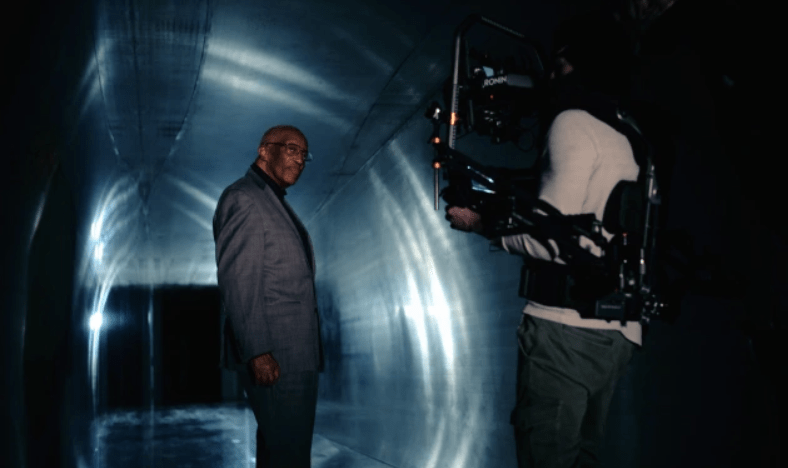

Dwight, who has been an active artist for years since leaving NASA a long time ago, reminisces about how much he had to cope with racial bias and prejudice right from when he joined NASA in the early 1960s. When he was going through the following training process under none other than Chuck Yeager, he often found himself pressured and ostracized a lot by many white people surrounding him, and Yeager himself was no exception. In fact, Yeager, who was incidentally Dwight’s longtime idol, actively tried to discourage Dwight by any means necessary, and that only made Dwight all the more determined to show his merit to Yeager and other white people.

In the end, Dwight eventually became a NASA astronaut officially, but then he had to face more difficulties on his way. Because he now became a sort of equivalent to Jackie Robinson in NASA, he had to be cautiously balanced about his public image, and he was even demanded to live again with his divorced wife just because of that. In addition, many black civil right activists pressured him more on being vocal about those civil right issues, but, not so surprisingly, that was not something he could easily talk about in public.

In the end, all of his hope was dashed when President Kennedy was assassinated a few years later. With no support from the White House, Dwight became more like a token astronaut than before, and this eventually made him leave NASA without looking back at all. Although he is now in peace with his past in NASA, Dwight cannot help but feel bitter about what he endured during that time, and we can only wonder how things would have turned out different if he had been allowed to go to the space just like many white astronauts during that time. As a matter of fact, US was actually behind the Soviet Union in that aspect, because the latter sent a black Cuban astronaut to the space in 1980 before the former eventually tried more racial inclusion in NASA.

Anyway, the Civil Rights Movement in the 1960s and the social/cultural prominence of African Americans in the following era came to open the door more for black astronauts. In addition, the subsequent development of space shuttles in the late 1970s boosted further the NASA space programs, and the NASA astronauts came to look relatively more racially diverse compared to how they looked in the 1950-60s.

Guion Bluford was one of notable black astronauts during the 1980s, and he and other black astronauts including Charles Bolden, who eventually became the first black Administrator of NASA in 2009, surely have a lot of things to tell us in front of the camera. Bluford recollects with some amusement on how he somehow got selected as the first African American sent to the space – and how much he and other black astronauts were excited to go to the space one by one. When one of the key members in the group was killed along with several other astronauts during that tragic accident in 1986, they were all quite devastated to say the least, but they kept going while trying to find out what went horribly wrong at that time, because that was exactly what that dead member would have done if he had been in their position.

Around its last part, which examines the current position of NASA black astronauts and their vocal opinion on the Black Lives Matter Movement, the documentary became relatively less fascinating. Yes, race issues are still serious matters in the American society even at present, and it is touching to see many black NASA astronauts showing some solidarity after the George Floyd incident, but this part feels rather weak compared to the rest of the documentary, probably because it looks less revealing in comparison.

In conclusion, “The Space Program”, directed by Lisa Cortes and Diego Hurtado de Mendoza, accomplishes its goal as much as intended in its short running time (90 minutes), and it will surely make a good double feature show with “Hidden Figures”, which touchingly presents the story of unsung colored female figures in NASA during the 1960s. Although I still wish the documentary could show and tell more, but that thankfully remains a minor flaw at least, and I think you should check it out someday.