The main subject of documentary film “Kim’s Video” is certainly something which will draw any serious movie fan’s attention. As a guy who spent a lot of time in a number of local video rental stores in my hometown when he was young and wild, I observed the story of one certain video rental store in New York City with some interest and fascination, but I must say that I was a bit disappointed to see that the documentary itself does not have enough depth to engage me.

During the early part of the documentary, co-director David Redmon, who also produced and edited the documentary along with his co-director Ashley Sabin in addition to handling its cinematography, reminisces about how movies have been a big part of his life since his childhood years in Texas during the 1980s. Once he got fascinated with movies, he devoured one movie after another just like I did during my childhood and adolescent years, and that eventually took him to New York City later.

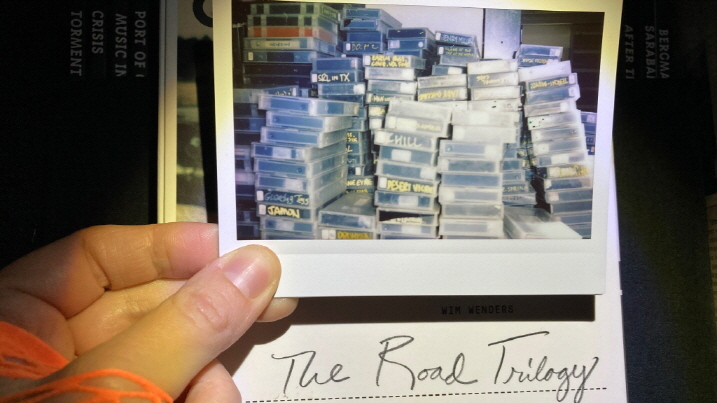

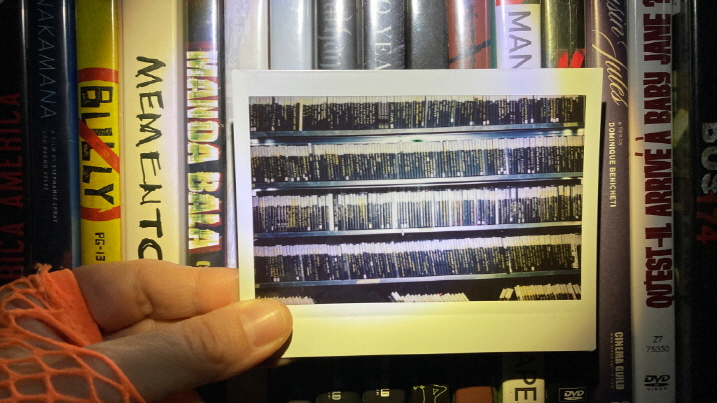

While living in the Brooklyn region, Redmon came to learn about Kim’s Video, which was a motherload of various types of movies to be enjoyed by many different movie fans ranging from the Coen Brothers to Alex Ross Perry. Established by a young South Korean immigrant named Yong-man Kim, who was incidentally once an amateur filmmaker, this huge video rental shop had thousands of VHS copies of various types of films, and we see a bit of how Kim and his employees tried to collect many different films inside and outside US as much as possible. As a matter of fact, they did not hesitate at all to commit copyright infringement in the name of love toward movies, and there is a little amusing episode involved with Jean-Luc Godard’s “Histoire(s) du cinéma” (1988).

Kim’s video rental business flourished during the 1980-90s as a part of the counterculture of New York City, but then its period was quickly over things began to change around the 1990s. As the era of digital medium began, VHS video tapes became less appealing even to hardcore movie fans, and, above all, what Kim’s Video had passionately done for years was slowly moving into the Internet. In the end, Kim decided to shut down his beloved video rental shop in the early 2000s, and its location becomes quite different now as shown from the opening scene of the documentary.

At least, Kim tried to save what he and his employees had passionately collected for years, and that was how the history of Kim’s Video got a stranger-than-fiction epilogue. Kim searched for any facility or institution which would willingly store all those VHS copies belonging to him, and, he eventually decided to hand them to a little city located in Sicily, Italia just because it looked like the city officials were eager to make his collection as a popular sight for tourists to come in addition to storing it with care.

However, when Redmon and his few crew members came to that city in 2017, it did not take much time for them to sense something fishy. To their surprise, Kim’s collection had been forgotten for years even though it arrived in the city with lots of fuzz in 2009, and the facility storing Kim’s collection had virtually been abandoned without much care or attention, though a security alarm was activated not long after Redman and his crew members sneaked into the facility at one point.

Redmon certainly tries to find out how Kim’s collection has been abandoned for years, and that is where the story becomes a bit weirder with a bit of the sense of danger. The transfer of Kim’s collection to that Sicilian city was involved with an untrustworthy local politician who may be connected with, surprise, the local Mafia organization, and this seedy politician certainly did not tell anything much to Redmon no matter how much he tried. Redmon got some information from several other local interviewees including one old prosecutor, but the mystery surrounding Kim’s collection remained elusive while becoming a little riskier than before – especially when one of the interviewees suddenly died not long after his interview with Redmon.

Of course, Redmon later approached to Kim, and they eventually met while Kim was attending some unspecified business meeting in South Korea, but Kim did not clarify the situation much to Redmon. Even at the end of the documentary, Kim remains as a rather vague figure even though he and his video rental shop are supposed to be the center of the story, and I wonder whether Redmon and his crew were quite limited from the beginning in case of getting to know more about Kim and his business.

During its last act, the documentary moves onto a little heist project planned by Redmon and several accomplices of his for saving Kim’s collection. This looks amusing at first, but I became more aware of the self-conscious attitude of the documentary, and I was also often distracted by Redmon’s frequent utilization of many different clips from a number of various films. He is indeed a big movie fan, and I understand that well as a fellow movie fan, but you may become annoyed like I did as he keeps comparing his journey experiences to a bunch of films such as “Blue Velvet” (1986) and “Goodfellas” (1990).

Overall, “Kim’s Video” may be worthwhile to check out if you have ever heard about its main subject, but the result is sometimes frustrating mainly due to its uneven and shallow narrative. Although the odd epilogue of the history of Kim’s Video is certainly interesting, the documentary could focus on who Kim really was or how much Kim’s Video meant to its employees and customers out there, and, in my inconsequential opinion, that would bring more depth to what happened to Kim’s collection in the end. Yes, it is surely driven by the love and passion toward movies, but, as many of you know, making a good and solid documentary needs more than that.