David Cronenberg’s 1983 film “Videodrome” is a grotesquely prophetic nightmare I still observe from the distance. There are a number of striking visual moments which have lingered on somewhere in my mind for more than 30 years, and they chillingly serve and amplify the interesting ideas and themes in the movie which become all the more relevant in our ongoing era of digital media. That is the main reason why I find the movie more fascinating than before, even while recognizing its several limits and flaws again.

At the beginning, we are introduced to Max Renn (James Woods), who runs a small UHF (Ultra-high Frequency) television station in Toronto, Canada. His company has mainly broadcast sleazy and sensational stuffs like Japanese softcore flicks, and he has always looked for anything more shocking just for drawing more viewers out there.

On one day, Max comes across something unusual via one of his main employees, who can search and then record anything via his pirate satellite dish. It is called “Videodrome”, and Max instantly gets intrigued because its raw presentation of sex and violence looks so real to him. When it later turns out that Videodrome has been produced somewhere in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, he becomes more interested in obtaining and then broadcasting it someday.

Needless to say, he is soon warned about how dangerous Videodrome is. Max’s frequent supplier Masha (Lynn Gorman) is reluctant to tell much about it after doing her own search, but she eventually suggests that he should go to Dr. Brian O’Blivion (Jack Creley), who has been known as a “media prophet” in public. Although he cannot meet Dr. O’Blivion for some reason, Max meets his daughter Bianca (Sonja Smits) instead, and she gives something supposed to help him learn more about Videodrome.

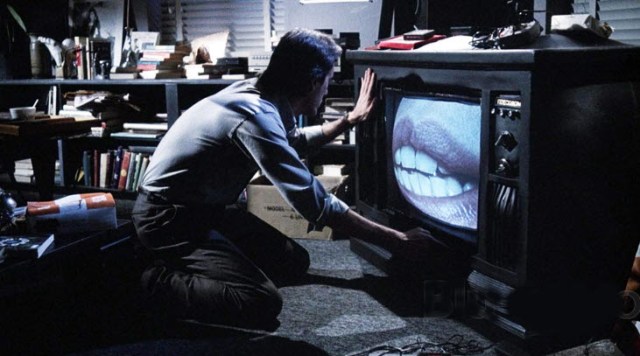

Around that point, the story becomes more confusing due to its hero’s gradually unreliable viewpoint, which is emphasized by a series of weird and grotesque moments including that unforgettable scene where he puts his head into the bulging television screen. The more he searches for the answer on who is really behind Videodrome, the more confused he becomes with the increasing sense of paranoia and doom. As a consequence, it is apparent that there is the only way out for him at the end of this nightmarish plight of his, though we are not so sure about whether that is really chosen by his free will or not.

However, I still feel quite distant to the story and characters. The story sometimes feels like a mere ground for its many unpleasant and freakish moments, and I also find that it does not have much depth in terms of characterization. James Woods and several other main cast members including Debbie Harry, Sonja Smits, Peter Dvorsky, Leslie Carlson, Jack Creley, and Lynne Gorman play their materials as serious and straight as possible, but I must point out that they are often limited by their superficial roles and clumsy dialogues full of mumbo-jumbo about Videodrome and the upcoming brave new world it represents.

Did Cronenberg have a clear vision on what he was going to present on the screen? I am not that sure, but the ideas and themes in his movie feel much more alarming and interesting than before. Like Sidney Lumet’s great media satire “Network” (1976), the movie shrewdly recognizes not only our insatiable thirst for shock and sensationalism but also how media can manipulate and then engulf us as providing whatever we want. As a matter of fact, we have seen such cases too often during last two decades thanks to the rapid rise of social media service, and the movie becomes a bit more ironic as Woods, who was supposed to be one of the most intelligent actors working in Hollywood, became one of those pathetic cases as spending too much time on a certain social media application and then being transformed into your average hateful right-wing weirdo.

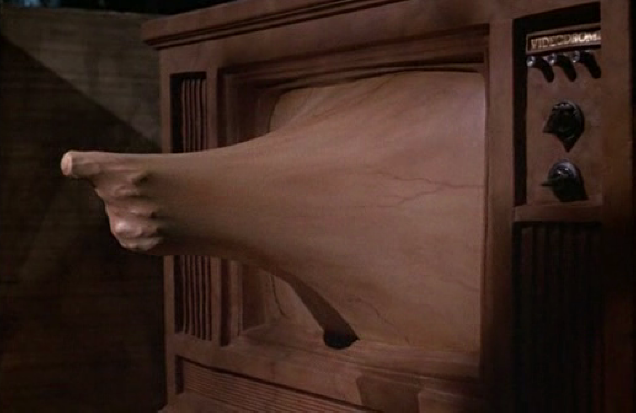

In case of technical aspects, the movie is impressive for the special effects by Rick Baker, who was already at the top of his field after winning his first Oscar for John Landis’ “An American Werewolf in London” (1981). Needless to say, many of the special effects in the film are not CGI at all, and their deliberately fleshy texture certainly generates more sticky and unpleasant feelings to the film just like Rob Bottin’s equally memorable special effects in John Carpenter’s “The Thing” (1982). Besides that bulging TV screen, you will never forget that grotesque cleavage suddenly appearing on Max’s belly, and you may be a bit amused by when Baker and Cronenberg seem to attempt to surpass Bottin and Carpenter’s achievement around the end of the movie.

In conclusion, “Videodrome” is everything to be recognized as a distinctive Cronenberg film, but I regard is as one of his early test runs just like “The Brood” (1979) and “Scanners” (1981), which are also interesting in each own way but not very successful in my trivial opinion. Not long after “Videodrome” came out, Cronenberg returned with “The Dead Zone” (1983), and that is more engaging besides being another stepping stone for his fascinating filmmaking career, which subsequently gave us “The Fly” (1986), “Dead Ringers” (1988), “Naked Lunch” (1991), “Crash” (1996), “A History of Violence” (2005), “Eastern Promises” (2007), “A Dangerous Method” (2011), and “Crimes of the Future” (2022). As shown from his latest work “The Shroud” (2025), he is still working as usual, and I sincerely hope that he will continue to disturb and fascinate us at least for a while.

![ERYRI [ Explore ! 08.03.26 ] ERYRI [ Explore ! 08.03.26 ]](https://live.staticflickr.com/65535/55136149619_b136b59fb3_s.jpg)