Japanese filmmaker Yasuo Furuhata’s 1999 film “Poppoya” is the story of one dedicated railway station master. While he has simply devoted himself to his menial occupation for more than 20 years without much complaint at all, he has also kept a lot of personal feelings to himself just for doing his professional duty day by day, and the movie is often poignant as gradually revealing his humanity along the story.

The early part of the film quickly establishes its hero’s early years. During the 1950s, Otomatsu Satō (Ken Takakura) was a diligent lad who worked as a train operator in some rural region of Hokkaido. Around the 1970s, his train company eventually promoted him a bit, and that is how he became the railway station master of one small coal mine village.

However, things have been recently not so good for Satō. After the coal mine was shut down several years ago, the village becomes far less populated than before, and then the train company decides to shut down the line. His close colleague suggests that he should move onto some other job just like him after his upcoming retirement, but Satō does not care much about that at all, while mostly being occupied with his daily job at the station as he has always been.

And we get to know more about his plain private life. He and his wife, who unfortunately died a few years ago, once had a daughter after many years of attempting to have a child between them, but, alas, their precious daughter died due to a sudden illness even before having her first birthday. Nevertheless, Satō kept focusing on doing his professional duty as usual, and this certainly hurt his wife’s feelings a lot, though she still loved and understood her husband.

While he has surely been lonelier since his wife’s death, Satō remains surrounded by his close colleague and several others who really care about him. Although he is not a very social person compared to his close colleague, many of his colleagues in the company regard him with a lot of respect and admiration because of his longtime professional dedication. In case of a sweet old lady who has ran a little restaurant in the village for many years, she has been pretty much like another family member to Satō, and there are a couple of moving flashback scenes showing how she came to take care of a little boy along with Satō and his wife after that boy happened to lose his single father due to an unfortunate mine accident.

While the weather gets a lot colder and snowier during what turns out to be his last winter season at the station, Satō continues to work as if nothing changed much, but there soon comes a number of small events unfolded around him. His close colleague visits him just for having a little drinking night along with him, and they naturally become a bit wistfully nostalgic about their shared past. In addition, Satō is visited by three different girls one by one when he is working alone by himself, and, though they are supposed to be the granddaughters of one of his village neighbors, he cannot help but become protective about them as being moved a bit by something special about them.

Steadily building up its story and characters bit by bit, the screenplay by Yoshiki Iwama, which is based on the novel by Jirō Asada, gives us more glimpse into its taciturn hero’s quietly beating heart. Just because of his unflappable sense of duty and pride, Satō has always restrained himself throughout his whole life, and the recurring memories of his wife and daughter lead him to more sadness and regret. Sure, he could have done better for them, but he and his wife also had some little happiness together in their married life, and there is a touching scene when he comes to have an unexpected moment of consolation later in the story.

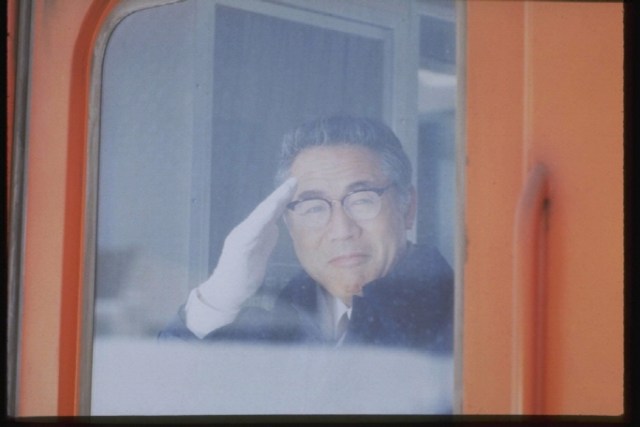

Needless to say, everything in the film depends a lot on the subtle but engaging lead performance by Ken Takakura, whom you may recognize for his notable supporting turns in several American films such as Ridley Scott’s “Black Rain” (1989). While looking quite dry and restrained in his low-key appearance, Takakura deftly conveys to us his character’s inner feelings without overstepping at all, and that is why several key moments in the film are so dramatically effective. Whenever Satō cannot help but show his emotions a bit, Takakura’s minimalistic acting shines with small human touches to observe, and we come to care more about his character than before.

Around Takakura, several other main cast members in the film come and go as functioning as livelier counterparts to his low-key acting. While Nenji Kobayashi provides some comic relief as Satō’s close colleague, Shinobu Otake brings a bit of precious human warmth to the story as Satō’s loving but fragile wife, and Yoshiko Tanaka, Ryōko Hirosue, Hidetaka Yoshioka, Masanobu Ando, and Ken Shimura have each own moment to shine along the story.

On the whole, “Poppoya”, which means “railroad worker” (鉄道員) in Japanese, is basically your typical sentimental melodrama, but it is tastefully handled via good mood and storytelling in addition to being supported well by the commendable efforts from its main cast members. Right from the beginning, you will clearly see where it is going, but you will be touched to some tears when it eventually arrives at its destination point.