Shunji Iwai’s 1996 film “Swallowtail Butterfly”, which happens to be re-released in South Korean theaters in this week, alternatively frustrated and fascinated me. While I admired its style and ambition, I could not care that much due to its broad archetypes and confusingly scattershot storytelling, and I only got more emotionally detached from it during my viewing.

At least, I appreciate how much Iwai attempted to do something quite different from his 1995 debut feature film “Love Letter”, a gently sentimental romantic film which has been embraced by both Japanese and South Korean audiences during last 30 years (It was re-released in both Japan and South Korea early in this year for its 30th anniversary, for example). In contrast to the tranquil melodrama of “Love Letter”, “Swallowtail Butterfly” often feels raw and wild in terms of mood and storytelling, and it works best whenever it focuses more on the details of its shabby futuristic world.

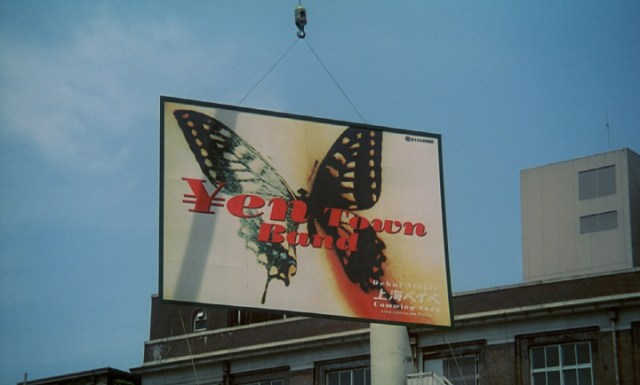

The movie is mainly set in Tokyo at an unspecific point in the near future. As the Japanese yen becomes the strongest global currency instead of the American dollar, many different immigrants come to Tokyo for realizing each own Japanese dream there, but they and their children often face the social discrimination from the Japanese natives. As Tokyo is nicknamed “Yen Town” (円都, en to) by the immigrants, the Japanese natives begin to call them “Yen Thieves” (円盗, en tou), a homophonic word which was anglicized as “Yentowns” in the English subtitle of the film.

The story begins with the death of one poor Chinese immigrant woman. Although how and why she died are not specified, her death leads to an unnamed daughter of hers being left alone by herself, and the early part of the film observes this unfortunate girl being moved from one spot to another in their slum neighborhood via a young Chinese prostitute named Glico (Chara). At first, Glico is going to sell the girl to a very unpleasant place for prostitution, but, as seeing that the girl is too passive and fragile for the job, she eventually changes her mind and then gets the girl hired by a sleazy Chinese immigrant dude named Fei Hong (Hiroshi Mikami), who incidentally runs a small illegal garage somewhere outside the city.

As the girl, who was named “Ageha” (Ayumi Ito) by Glico (It means “swallowtail” in Japanese, by the way), tries to adjust herself to her new life condition, we get to know more about the people around her and their slum environment, which is quite vividly and realistically presented on the screen. Although the futuristic background of the film is not so grand or flashy compared to Ridley Scott’s “Blade Runner” (1982) or Terry Gilliam’s “Brazil” (1985), its numerous shabby places are accompanied with enough mood and details to intrigue us, and the characters in the movie really look like having been inhabiting their gloomy (and trashy) world for years.

Needless to say, Fei Hong and his associates are very eager to grab any chance to earn a lot of money from their very poor economic status and such an opportunity fortunately comes at one point in the middle of the story. He comes across a rather clever way of currency counterfeit, and he and others around him are certainly quite excited about whatever may be possible via this criminal means.

With that counterfeited money of his, Fei Hong later purchases a local nightclub for promoting Glico as a new promising singer, and their plan actually worked much better than expected. Not long after her first performance at the nightclub, Glico takes a big step toward more career success, but this success of hers consequently puts some distance between her and others including Fei Hong and Ageha.

Meanwhile, the movie occasionally sways into a subplot involved with a bunch of Chinese mafia gang, who have been looking for a certain valuable cassette tape which happened to be acquired by Fei Hong when he tried to handle some big problem for Ageha and Glico early in the film. As clearly shown from his first scene, the boss of the Chinese mafia gang is quite determined to get that cassette tape by any means necessary, and it is apparent that his organization will come upon on Fei Hong and others sooner or later.

Around that narrative point, we are supposed to be engaged more in the narrative of the film. However, Iwai’s screenplay often stumbles as being too busy with juggling many different plot elements together, and we frequently get confused and befuddled while not really getting to know or understand its main characters. For instance, even when she comes to open herself more during the last act, Ageha remains as an elusive cipher, and many other main characters around her are mere stereotypes on the whole. In addition, there is some potential for melodrama when it turns out that there is a hidden personal connection between a certain main character and the Chinese mafia boss, but that remains under-developed to our dissatisfaction, and the same thing can be said about the unexpected emotional bond between Ageha and Fei Hong.

Overall, “Swallowtail Butterfly” is often hampered by a number of flaws including its overlong running time (148 minutes), but it is an interesting exercise in style which may engage and then impress you more. Although I am still less enthusiastic compared to other reviewers and critics, the movie does have ambition, and that is surely something to be admired and appreciated.