Documentary film “Ryuichi Sakamoto: Opus”, which was premiered in the Venice International Film Festival several months ago and then will be released in South Korean theaters in the last week of this year, is quite simple in its presentation setting. At first, it seems to observe merely what turned out to be the last performance in the long and illustrious career of Ryuichi Sakamoto (1952 ~ 2023), but it did a commendable job of vividly capturing a number of undeniably powerful artistic moments to linger on our minds, and the overall result is often very poignant to say the least.

As many of you remember, around the time when Stephen Nomura Schible’s documentary “Ryuichi Sakamoto: Coda” (2017) came out, it seemed that Sakamoto was on the way to recover after getting the medical treatment on a serious case of throat cancer. Unfortunately, he was diagnosed to have another kind of cancer a few years later, and he had to go through another medical treatment, but he eventually died early in this year to our sadness.

Several months before his death, Sakamoto embarked on his last project along with director Neo Sora, who is incidentally Sakamoto’s son. After selecting and then arranging 20 pieces from his vast body of works, he did a solo piano performance all by himself during a series of sessions at his favorite recording studio in Tokyo, and he could actually watch the final cut version of his son’s documentary not long before he passed away.

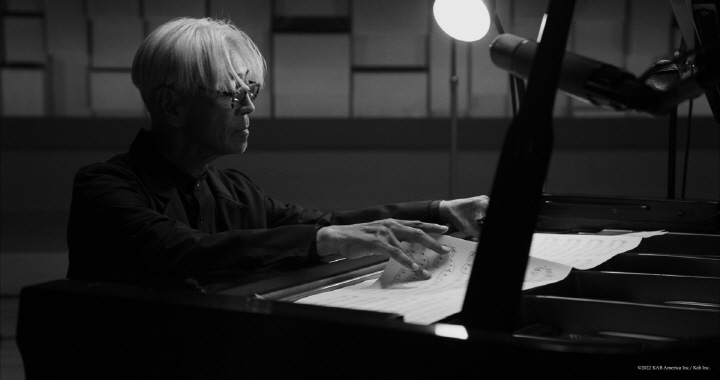

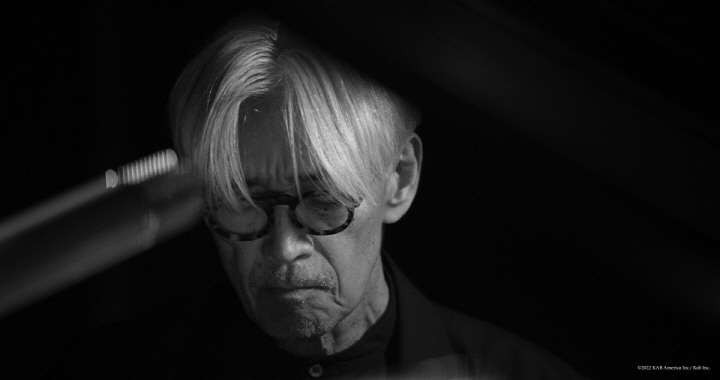

Without any introduction or explanation, the documentary just shows Sakamoto performing a Yamaha piano in the middle of the studio from the beginning to the end, but Sakamoto’s solo piano performance slowly draws our attention in the middle of the quietly isolated environment of the studio, which is further accentuated by the strikingly stark black and white cinematography by Bill Kirstein. Whenever the camera closely observes Sakamoto’s performance, we cannot help but feel some melancholy from his rather weary appearance, and, though he does not signify much on the surface, it seems that he knew well that the end of his life was quite imminent. In fact, we are reminded more of his impending death whenever the documentary looks at his face immersed in lights and shadows generated by a few lighting equipments inside the studio.

His considerable physical vulnerability during these recording sessions is particularly evident when he is performing “Bibo No Aozora”, which was powerfully utilized in the heartfelt final scene of Alejandro González Iñárritu’s great film “Babel” (2006). In the middle of the performance, he unexpectedly makes a glaring error to our surprise, and I found myself bracing myself at times while observing his following struggle to regain the control on his performance. He wanted to do it again, but his son chose to include this flawed take in the documentary, and that is the right choice considering that Sakamoto was ready and willing to present himself in front of the camera with no ego or pretension at all.

Although most of the works performed by Sakamoto in the documentary are unfamiliar to me, I could easily recognize the main themes of his several notable film scores at least. While the Oscar-winning score for “The Last Emperor” (1987) surely gives us one of the highlight moments in the documentary, the score for “Merry Christmas Mr. Lawrence” (1983) lightens up the mood a bit around the end of the documentary, and the score for “The Sheltering Sky” (1990) provides another enjoyable moment in the documentary.

There are also a number of brief interludes during which Sakamoto occasionally says a few words or silently prepares for whatever he is going to perform next. Many of these moments feel rather inconsequential on the surface, but there is one short but interesting moment to remember. At one point, we see how he puts some devices onto the piano strings for a bit of sound manipulation, and the following sonic result is deliberately jarring but interesting for our ears nonetheless.

Meanwhile, we come to admire more of his considerable artistic dedication as the camera frequently shows Sakamoto’s aged hands and fingers. After that glaring moment of error, we observe more of how his performance feels a little shaky and unstable from time to time, but he is not daunted by that at all as far as I can see from his mostly calm and phlegmatic face. The mood naturally becomes more bitter and gloomier as his showtime is being over, but he keeps going as before, and the documentary closes with a sublime moment which reminds us that his artistic achievement will remain as long as we remember and cherish what he created during last several decades.

On the whole, “Ryuichi Sakamoto: Opus” is worthwhile to watch for not only the gracefully humble qualities of Sakamoto’s last performance but also how it is sensitively and thoughtfully presented on the screen with lots of care and respect. To be frank with you, I am not a very big fan of his films scores, but I came to admire him all the more than before after observing more of his artistry and humanity via “Ryuichi Sakamoto: Coda”, which I sincerely recommend you to check out before watching “Ryuichi Sakamoto: Opus”. I assure you that these two good documentaries will make an interesting double feature show for you, and you may also want to check out more of his works after watching them.

Pingback: 10 movies of 2024– and more: Part 2 | Seongyong's Private Place