Netflix film “Rustin”, which came out in last week, wants to be two different things at once, but I do not think it succeeds as much as intended. On one hand, it wants to present a monumental historical event of the late 20th century American political history via the viewpoint of a certain openly gay figure who deserves to be known more, but it does not bring much new insight to be added to what I have learned from many different (and better) movies and documentaries. On the other hand, it also wants to explore who this interesting figure really was, but it only feels like scratching the surface despite the considerable efforts from its lead actor.

Colman Domingo, who has been quite more notable during last several years since his substantial supporting role in Barry Jenkins’ “If Beale Street Could Talk” (2018), plays Bayard Rustin, an African American civil rights activist who was one of the key figures behind the March on Washington in 1963 but did not get much recognition during his lifetime for an unfair reason. As shown right from the opening part of the film, his homosexuality was an open secret among many of his colleagues including Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. (Aml Ameen), and that was the main reason why he came to resign from his post in NACPP (National Association for the Advancement of Colored People) in 1960.

Three years later, Rustin is brought back in action once it looks like the Civil Rights Movement led by Dr. King and other prominent activists really needs a public boost for their noble cause. Although they have certainly gotten some support from President John F. Kennedy and many other liberal white politicians, that is still not enough for them nonetheless, and Rustin has one bold idea for drawing much more public interest on their cause. He proposes a massive political rally in the middle of Washington D.C., but many of his colleagues are skeptical about whether they can actually pull it off due to several understandable reasons. First, they need to organize and prepare for everything within a few months, and Rustin and his close colleagues also will have to deal with not only those staunch white officials but also certain prominent African American figures who do not like Rustin much.

The most interesting part of the film shows how hard and difficult it was for Rustin and his colleagues to coordinate among NACCP and many other political organizations involved with the Civil Rights Movement, each of which was not easily persuaded to gather together from the very beginning. At least, Rustin succeeds in persuading Dr. King to work with him as before, and his several old colleagues are also ready to help and support him as much as possible, but then they often feel like facing the dead end as they try to balance their big political project among NACCP and many other groups.

However, Rustin still sticks to his goal even though he is well aware that his homosexuality will definitely be a liability in one way or another, and he does not hide his homosexuality at all even at that point. He continues to live with a white activist who is more than a personal assistant of his, and he also does not mind at all when a certain young handsome African American pastor approaches closer to him in private for the reason they cannot openly tell outside. Although this guy is actually married, Rustin does not care much about that as long as he is willing to spend more time with Rustin.

As swinging back and forth between these two different narrative lines, the screenplay by Julian Breece and Dustin Lance Black attempts to delve more into its hero, but the result unfortunately feels shallow and scattershot at times. While many notable real-life figures besides Dr. King come and go around Rustin along the story, we seldom get the full picture of their preparation for the March on Washington in 1963, and the presentation of their strenuous efforts and the following eventual result is somehow flat and superficial while looking more like your average history lesson. In case of the part involved with Rustin’s personal life, we surely get some glimpses of Rustin’s struggle as an African American gay man, but the movie does not go further from that, and it also fails to generate enough emotion from Rustin’s rather complicated relationship with his long-suffering white companion.

The movie works whenever Domingo’s solid lead performance takes the stage, and he surely brings enough life and spirit into his several big scenes. Although he looks rather silly and flamboyant at first, Domingo gradually adds human nuances and details to his role, and he did a credible job of embodying his character’s irrepressible will and charisma while ably carrying the film to the end.

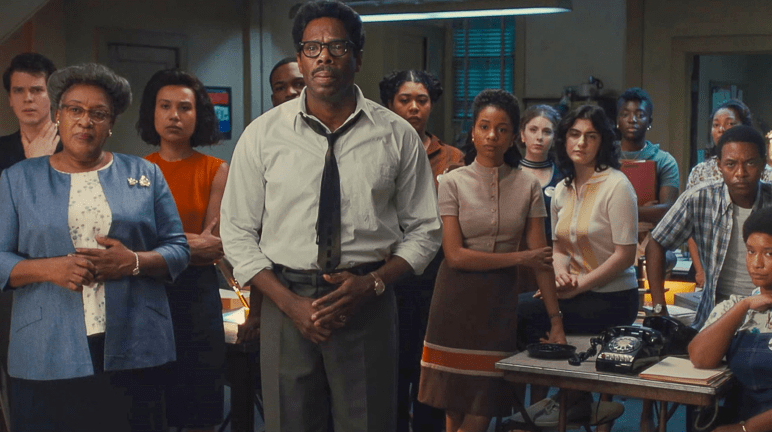

In case of several notable supporting performers in the movie, they mostly acquit themselves well despite their under-developed roles. While Chris Rock and Aml Ameen are occasionally rather strained, Glynn Turman, Michael Potts, Audra McDonald, CCH Pounder, and Jeffrey Wright are reliable as usual, and Da’Vine Joy Randolph, who has drawn more of my attention since her delightful breakout supporting turn in “Dolemite Is My Name” (2019) and may soon be on the road to Best Supporting Actress Oscar thanks to Alexander Payne’s “The Holdover” (2023), briefly appears as Mahalia Jackson around the end of the film.

In conclusion, “Rustin”, directed George C. Wolfe, is not so satisfying in many aspects. While it is less entertaining than Wolfe’s previous Netflix movie “Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom” (2020), its depiction of the Civil Rights Movement is less compelling than several similar films such as Ava DuVernay’s “Selma” (2014), and it is also less engaging as a queer drama compared to Gus Van Sant’s “Milk” (2008), which incidentally garnered Black a Best Screenplay Oscar. To be frank with you, I would rather recommend any of these three films instead, but Domingo’s diligent work here in the film makes the movie watchable to some degree, and you may come to hope that there will be better things in his advancing acting career just like I do.

Pingback: My Prediction on the 96th Academy Awards | Seongyong's Private Place