Errol Morris’ latest documentary “The Pigeon Tunnel”, which is currently available on Apple TV+, focuses on the life and the works of John le Carré via le Carré himself, who incidentally passed away in 2020 not long after interviewed by Morris. While he remains mostly discreet and elusive throughout the documentary, le Carré is still a fascinating figure nonetheless, and it is often engaging to observe how he and Morris subtly push and pull each other as Morris attempts to draw more from him.

At first, the documentary mainly revolves around how the early years of le Carré’s life made him ready for writing as well as that cold world of espionage. He was born as David John Moore Cornwell, and he frankly recollects on how his early years were often rocky thanks to his criminal father, whose big financial schemes frequently threw his family into one trouble after another. As a matter of fact, le Carré’s mother left her husband and her son without never looking back because of not only this but also his frequent womanizing, and le Carré reunited with his mother only after he came to know her whereabouts many years later.

At least, le Carré’s father made sure that his two sons got good education at prestigious private schools, but le Carré always felt like an outsider even though he mostly went along well with his schoolmates. Constantly aware of his rather shameful family background, he usually felt like an imposter in the bunch, and it goes without saying that this was how he was shaped up to become ideal for espionage later.

Not long after he began to study in Oxford University, le Carré was secretly recruited by a member of the British intelligence agency. At first, he worked for MI5, but then he moved to M16, which handles international matters in contrast to MI5 handling the domestic ones. While he officially worked as a diplomat in Berlin on the surface, he often did some espionage works behind his back as watching the construction of the Berlin Wall in the early 1960s, and that was the main inspiration for his third novel “The Spy Who Came in from the Cold”, which put him right on the top of espionage fiction thanks to its huge commercial/critical success.

As reminiscing about how he worked for MI6 during that time, le Carré dryly observes on the qualities necessary for being a spy. Besides being able to become a liar and con man, a good spy is also required to have enough loyalty for serving his/her master all the way, and le Carré happened to have the right stuffs for that. While he had much more integrity than his father, he was also not so different from his father in some aspects, and he indirectly recognizes his less wholesome aspects as reflecting on how he was pretty good at deception just like his father.

During the same time, le Carré also went through more development as a storyteller, and his direct experience with the Cold War espionage was certainly a rich source for his considerable storytelling talent. Even when he was young, he was quite interested in creating narratives out of his life, and he frankly admits how he sometime deceived even himself in that way. For example, one of his writings describes a rather Dickensian moment involved with his father’s imprisonment, but that moment never happened actually. As le Carré sharply points out, this surely exemplifies well how much we easily deceive ourselves for making any sense out of our usually messy life.

While still not liking his father that much even at present, le Carré let himself often take care of his father’s small and big problems, though there eventually came a point where he decided that enough is enough. His longtime desire for a better father figure led to the creation of his famous spy character George Smiley, but you can see bits of le Carré himself from Smiley when he occasionally reveals his strong sense of morality – especially in case of one moment when he sharply talks about a certain infamous British double agent who is clearly the main model for the mole character in his acclaimed novel “Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy”.

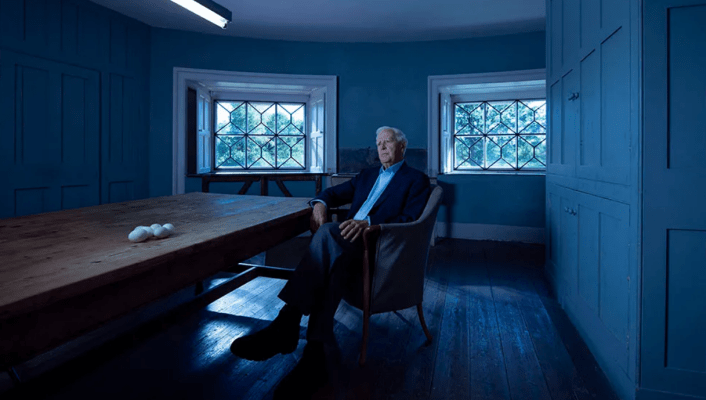

Although seemingly telling a lot about his life and career, le Carré remains as a deeply private person not so willing to tell everything in front of the camera, and we come to sense more of the underlying tension between him and Morris as Morris occasionally asks some questions to le Carré. While admitting that what he has told to Morris may not be entirely true, le Carré does not go further even when nudged a bit by Morris, and the remaining ambiguity surrounding him is further accentuated by the coldly rhythmic score by Philip Glass and Paul Leonard-Morgan.

On the whole, “The Pigeon Tunnel”, which is derived from le Carré’s usual temporary title for his work in progress, may disappoint you to some degree because it does not reveal everything about le Carré’s life and career, but it is still worthwhile to watch mainly thanks to le Carré’s fascinatingly reserved presence, and Morris did a skillful job of mixing le Carré’s insightful words with a number of various archival records and clips, while often peppering the resulting mix with the recurring images associated with the origin of that temporary title of le Carré. Morris may not wholly succeed in his approach to le Carré, but le Carré is indeed one of the most interesting human figures interviewed by Morris, and that is more than enough for me for now.