David Lynch’s 1999 film “The Straight Story”, which happened to be shown in selected South Korean theaters along with his several other works in last week, shows Lynch at his most sincerely heartfelt. While many of his works are filled with dark, strange, and disturbing surrealistic elements, there is also a considerable amount of sincerity which sometimes seems to you as corny and clichéd as a piece of cheery pie and a cup of black coffee as shown from “Blue Velvet” (1986) or his cult TV series “Twin Peak”. With the gently sincere and haunting sensibility of “The Straight Story”, he demonstrates here that there has indeed been heart behind his darkly wild style and imagination from the very beginning of his filmmaking career, and this modest but special film can be regarded as an important artistic breakthrough as much as his subsequent film “Mulholland Drive” (2001).

The movie, which is based on the true story of an old man named Alvin Straight, begins with the opening scene which evokes a bit of “The Elephant Man” (1980) and “Blue Velvet”. At first, we see the big and wide sky full of shining stars which will surely take you back to the ending of “The Elephant Man”, and then the movie looks over and around a small little town in Iowa which looks and feels not so different from that suburban world in “Blue Velvet”. However, nothing serious or ironic or disturbing happens on the screen in this time, except a sudden little medical problem for Straight, played by Richard Farnsworth.

Once his daughter Rose (Sissy Spacek) and his neighbors find him collapsed on the floor, Alvin is subsequently taken to a local hospital. His doctor advises that he should pay more attention to his aging body which may stop functioning at any time, but he does not follow the doctor’s advice at all while continuing his usual lifestyle as before. He keeps doing his daily stuffs, and Rose, who incidentally has some mild mental retardation, is always around him whenever she is not working on birdhouses.

And then there comes an unexpected news from Wisconsin. Alvin’s estranged brother Lyle (Harry Dean Stanton) had a serious case of stroke, and Alvin comes to decide that he should really go to see Lyle, though they have never talked with each other for around 10 years due to some personal clash between them. Because of his weak eyesight and fragile legs, driving is out of question for him from the beginning, and there is no direct bus going to where Lyle lives, so Alvin eventually decides to use his old lawn mower for his long journey from Iowa to Wisconsin.

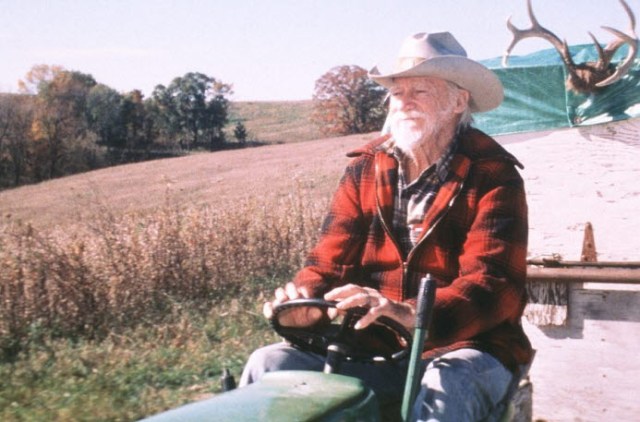

Although there is some amusement during the first days of Alvin’s journey, the screenplay by editor/co-producer Mary Sweeney and her co-writer John Roach sticks to its plain sincere attitude as before. When his lawn mower turns out to be not so reliable not long after he leaves his town, Alvin simply buys another lawn mower and then starts the journey again. The lawn mower can only move at a maximum speed of 5 miles per hour (8.0 km per hour), and he will have to cross over the distance of 240 miles (390 km), but he is not daunted at all as patiently driving along the road to his brother’s place.

Just like many other road movies out there, the movie doles out a series of episodic moments as he meets a number of different people one by one along his journey, and Lynch presents them with a considerable amount of restrained sensitivity. For example, when Alvin comes across a young female hitchhiker, we are not so surprised that they eventually spend a night together, but we are later touched by how sensitively the movie handles the brief but meaningful conversation between them. In case of a scene involved with one particularly unlucky woman who seems to come from a usual Lynch film, the movie surprises us as thoughtfully and empathically regarding her anger and pain along with Alvin, and then we get a little genuine laugh from how he takes care of the mess from her another unfortunate accident.

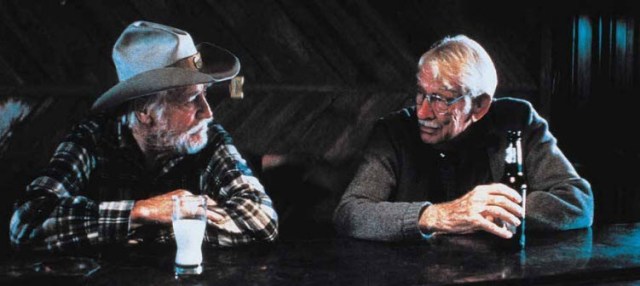

And we get to know more about Alvin and his past. It is revealed later in the story that he fought in World War II, and there is a quiet but powerful moment when he reveals a bit of his personal demon as talking with an old man who understands him well as a fellow World War II veteran. The camera simply focuses on his rough and wrinkled face during this moment, but we become more engaged, while sensing more of his old personal pain from the past.

Leisurely rolling the story and its hero along its mildly eventful narrative course, Lynch and his crew fill the screen with the warm and gentle rural atmosphere you can expect from the midwestern American background of their movie. While cinematographer Freddie Francis, who previously collaborated with Lynch in “The Elephant Man” and “Dune” (1984), did a splendid job of presenting wide and beautiful landscapes with unadorned realism and poetic beauty, and the score by Angelo Badalamenti, who was also one of Lynch’s main collaborators, is appropriately folksy at times as subtly capturing the emotional line of the story.

Above all, the movie depends a lot on the wonderful lead performance from Farnsworth, who was Oscar-nominated not long after his death. Thanks to his nuanced acting, we come to sense more of his character’s humanity along the story, and he is especially terrific during a mildly amusing scene where his character tells something important to the two brothers working on his broken lawn mower. He does not sound preachy or condescending to them at all as simply talking a bit about his relationship with his estranged brother, and those two brothers clearly get the point even though they say nothing at all.

Around Farnsworth, a number of various supporting performers simply come and then go along the story, but they are quite believable as the real people you may encounter while you travel across the midwestern American regions. In case of Sissy Spacek and Harry Dean Stanton, they are reliable as usual while functioning as the crucial parts of the story, and Stanton, who is virtually Colonel Kurts of the story, is effortlessly poignant with Farnworth during the expected finale.

Overall, “The Straight Story” is surely quite an abnormally plain, humane, and normal work in Lynch’s idiosyncratic filmmaking career, but it is much more than that. Just like the Coen brothers in “Fargo” (1996), Lynch came to show more heart than before here in this little but exceptional movie, and I believe that was really vital for the critical success of “Mulholland Drive”, where he finally hit the right balance between his nightmarish genre exercise and the sincere aspects of his distinctive artistic sensibility. In my humble opinion, the movie deserves to be admired and cherished as much as many of Lynch’s other works, and I assure you that you will not forget its aging human hero after watching it.