For many years, watching Jean-Luc Godard’s ground-breaking film “Breathless” has felt like homework for me. To be frank with you, I usually prefer François Truffaut’s movies to Godard’s, and I usually find many of Godard’s films rather cold, haughty, and distant, though I admire some of his early works including “Vivre sa vie” (1962) and “Band of Outsiders” (1964).

However, my impression on “Breathless” is changed a bit now, probably because I recently watched Richard Linklater’s “Nouvelle Vague” (2025), which is a lightweight dramatization of the making of “Breathless”. As watching “Nouvelle Vague”, I came to have more understanding on what Godard boldly attempted to do at that time, and that makes me appreciate more of that precious lightning captured inside “Breathless”.

Even before “Nouvelle Vague” came out, the story behind the making of “Breathless” has been known well to many of us for many years. Godard wrote the screenplay from the story conceived by Truffaut, but he and his cast and crew members frequently depended on instant improvisation, as he tried to break all the conventions and rules for making something different just like many of his fellow critics of Cahiers du Cinéma who became the leading figures of the French New Wave during the 1960s.

As amusingly shown in “Nouvelle Vague”, even Godard seemed not to know what exactly he was trying to make with his cast and crew, but his audacious cinematic gamble led to one of the most important breakthroughs in the movie history. Yes, he and the movie changed the vocabulary of cinema forever via the bold and unconventional utilization of jump cut, and its frequent jump cuts still catch our attention with the sheer audacity actually coming from practical reasons (He needed to shorten the movie to a considerable degree during the post-production period, you know). At the same time, we are drawn more to the raw energy and excitement generated by its defiantly free-flowing narrative and its two broad but undeniably compelling lead characters, and you may come to understand more of whatever Godard has attempted since this remarkable first feature film of his.

One of the two lead characters in the film is Michel Poiccard (Jean-Paul Belmondo), a young small-time car thief who is a textbook case of “style-but-no-substance”. Whenever he is not doing anything criminal, he often tries to imitate those gangster characters of the Hollywood movies from the 1940-50s, and this aspect is particularly evident when he looks into the photograph of Humphrey Bogart for a while at one point in the middle of the story.

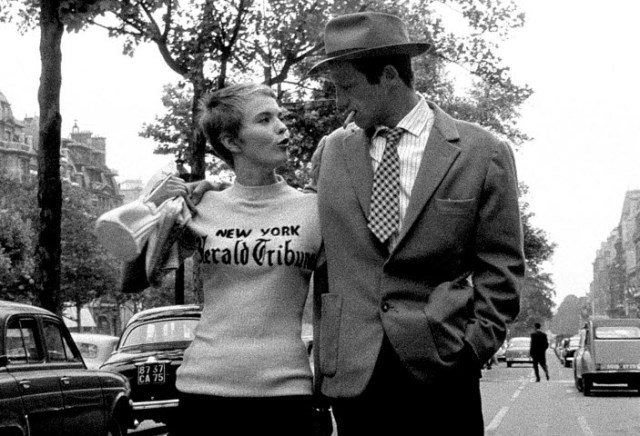

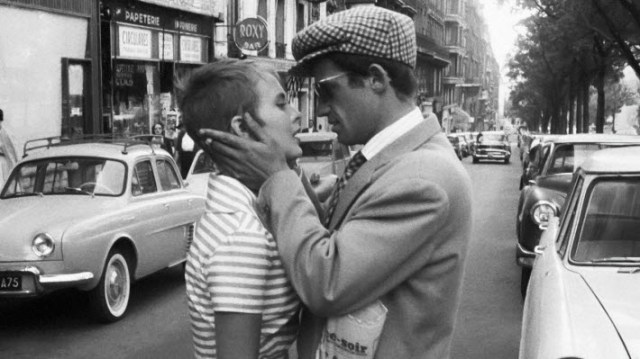

At the beginning of the story, Michel gets himself into a very serious trouble. Not long after stealing another nice big car, he finds himself pursued by a couple of police officers, and he inadvertently killed one of them. Needless to say, he becomes quite desperate as looking for any chance to grab some money to help his getaway, but then he gets irresistibly attracted to Patricia Franchini (Jean Seberg), a young and beautiful American who has aspired to be a newspaper journalist while also being about to enroll in Sorbonne University in Paris.

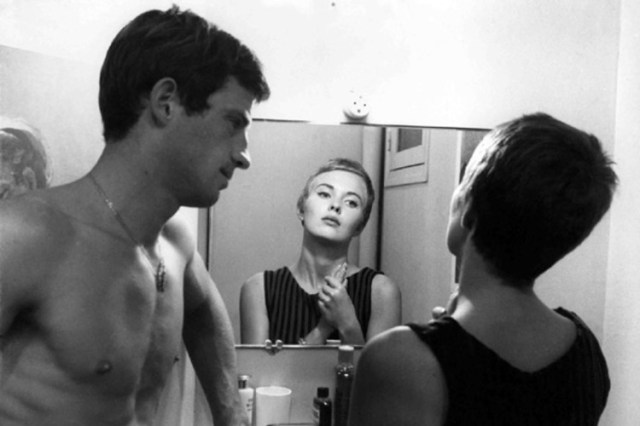

Most of the movie focuses on the offbeat romantic interactions between these two different figures. Even though the time keeps running out for him, Michel wants to spend more time with Patricia, but Patricia remains rather distant to him even though it is apparent that she is intrigued by his vapid but amusing panache. Their romantic tension eventually culminates to an assured long-take scene unfolded inside Patricia’s little residence, but, again, Patricia keeps her counsel to herself as much as Michael Corleone. While both of them just began their respective movie acting careers before appearing together in the film, Jean-Paul Belmondo and Jean Seberg effortlessly complement each other as fully embodying their respective archetype roles, and their iconic characters certainly opened the door for many other similar movie couples such as, yes, the titular characters of Arthur Penn’s equally great breakthrough film “Bonny and Clyde” (1967).

Meanwhile, the movie cheerfully bounces from one narrative point to another as occasionally adding a series of self-conscious touches to amuse you. You will smile a bit when Cahiers du Cinéma briefly appears early in the film, and Michel’s occasional alias, Laszlo Kovacs, is the name of Belmondo’s character in Claude Chabrol’s 1959 film “Web of Passion” in addition to being the name of a well-known Hungarian cinematographer. While cinematographer Raoul Coutard brings a lot of realism and verisimilitude to the screen via several unorthodox shooting methods used by him and Godard (He even shot one certain scene while hiding inside a rather small wooden box, for example), the care-free attitude of the movie is often accentuated by the jazzy score by Martial Solal.

In the end, like many other criminal movie couples, Michel and Patricia come to face the inevitable end of their deviant fun and excitement, and that is where the movie becomes a bit elusive. In what can be regarded as a pretty self-serving act, Patricia comes to betray Michel, and Michel leaves a little gesture along the very bitter final word at the end of his casual but undeniably striking death scene. While Coutard’s camera looks into Patricia’s face at the very end of the film, Patricia remains elusive as before, and we keep wondering where her heart really lies.

On the whole, “Breathless” still feels young and spirited just like many other great films such as Orson Welles’ “Citizen Kane” (1941), and it will surely take you back to the time when Godard was really cool and interesting. I still have reservation on most of his later films including “Goodbye to Language” (2014), but he did contribute a lot to cinema at least when he was young and wild, and we can still appreciate that.